coding as art

Aesthete and Ctrl+Alt+Delete

Mild annoyance or chuckles of derision are the most frequent responses I get from my art/humanities friends when I tell them I think of coding as an art form. And I have many of these friends, having considered myself very much a musician/writer first and STEM person second for many years (including the majority of my time spent studying physics as an undergraduate). And, for what it's worth, a lot of these friends are highly STEMmie people. Some of them are drummers-plus-computer scientists. Some of them are physicists who play guitar (the overlap is ridiculously large and not talked about enough).

Some of them, however, are through-and-through humanitarians with serious bona fides- First Class music grads from prestigious conservatories, early-career socialistic political operatives, published authors, essayists, more; a diverse bunch who are unified in their hatred of the Command Line Interface.

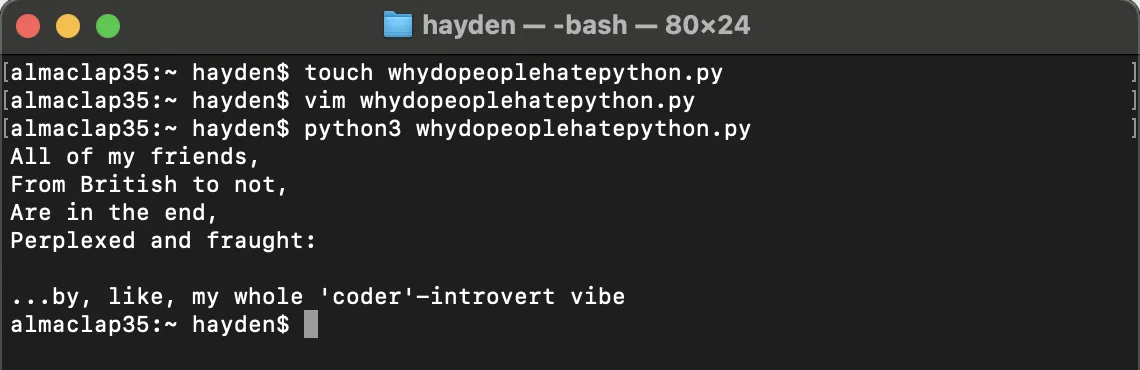

Don't BASH it 'til you try it

Don't BASH it 'til you try it

Usually I get further in the argument than you'd expect, mostly due to some arty bona fides of my own, but I never actually win. I appeal to people who've done what I've done a million times- sit down in a silent room and try to write a song from scratch. People who, like me, have often found themselves excited by the look of a blank screen in a word processor, or who've found themselves smiling to no one but themselves when they hear three of their new chords together for the first time, doing something that no one else in the world could possibly do, not even after a hundred years, because a butterfly flapped its wings in Minnesota and a wave broke against the artificial reef in Amalfi and the sum total result is that you, here, right now, did something completely new, and it somehow came straight out of you, unprompted. And you can never really choose those moments, they just come to you, and when it's done, and even when you've run out of ideas, still, there, on the page or in your voice memos, there it is, something you've done, and you count on those moments and those notes and those words when you're somewhere you've never been before and farther away from anyone you know than you've ever been. "Look," we say. "I did something. I did it."

The most exciting moment is the one before you write on the page.

The most exciting moment is the one before you write on the page.

I won't wax lyrical about the democratisation of knowledge and resources brought about by the emergence of the internet, and the World Wide Web after it. Smarter, sharper, and more patient minds than mine have long since done that topic adequate justice. But there is something irrefutably romantic about the fact that you can sit anywhere in the world and, with a good enough internet connection and a Python distribution, do anything you set your mind to. Somewhere, with just 104 different keys, you can build a state-of-the-art algorithm for predicting house prices in Palo Alto, or write the Great American Novel Pynchon didn't quite manage. Why we choose to bifurcate these two experiences, coding and creating, I honestly don't know. It's not a misconception that exists in circles of coders or in the rooms of CTF competitions. It takes panache, resilience, spark, and flair to write a good binary exploitation, the same way it takes all of those things to be a great author, to be a great musician.

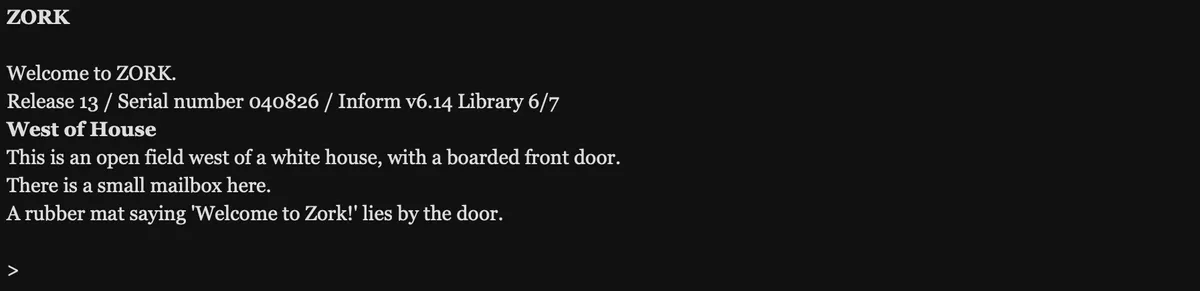

I remember when I wrote my first couple of serious computer programs. I was nine. For a large part of my childhood, I had spent my nose buried in Northern Lights, Hitchhiker's Guide, or Lord of the Rings. I read a lot of books and I played a lot of video games. And especially near-and-dear, Zork, the world's first true work of interactive fiction, a form of computer game where there is little or no graphical interaction with the user, and it's just you and plaintext, some omniscient narrator telling you that you are standing outside of a house.

One of the most famous paragraphs of all time, and one that I probably use to know by heart.

One of the most famous paragraphs of all time, and one that I probably use to know by heart.

I spent a lot of time up North, too. Places like Scotland and Durham, where my family are from, cold places that capture the imagination the way the sandy Cotswold limestone of those spires do in my hometown, Oxford. So I would sit, either in campsites or at my desk at home long after I'd come back from Castle Urquhart or Loch Ness typing out my own versions of Zork, versions of the world where my holiday ended in subterranean networks underneath Inverness, or versions of my hometown where large buildings rose from the ground if you pulled the right branch in the park behind my house. It wasn't C or Python, but it was coding- I designed projects, had to check my syntax and indentation, and I had to test for bugs- so much the better that the debugging took the form of play-testing. I was always more interested in building games than playing them, or writing things instead of reading them. I didn't need a typewriter or a literary agent or a job, just a computer- any computer, you don't need much memory to do a lot- and I guess some things never change, because fourteen years later I'm still doing much the same thing, except now I'm too tired and jaded to remember what it first felt like.

One of my friends is a writer. A bloody good one, too- I can barely understand what he's writing, even when he's writing about things that I understand. One can be forgiven for thinking that makes me unfit to write, the same way a lot of people feel unfit to boot up a terminal and start working with code. But it doesn't work like that. Stare long enough at anyone's code, and you'll find mistakes. Stare long enough at the work of the greatest writer, and you'll find awful ideas that embarrass even them. Everyone is paralysed by the fear of making mistakes, or veering out of their "lane", whatever that might mean, into something that isn't "right" for them. It's the same reason so many of my coder friends never bought themselves Squier Stratocasters even though they admire Kurt Cobain, the reason my friends resist the urge to smash my Macintosh every time they see me type cd ~ into a CLI. I don't think the human brain works the way we think it does- I don't think we really have these built-in limitations that make us only physicists or only singers. I think we have this learned sense of fearing failure or embarrassment, instead, and I think that's why none of us think of ourselves as artists, even though pretty much all of us are, in some way or another.

The sky over Geneva has gone a deep indigo, right now. Earlier I was watching the planes pass my window. Someone out there had to build all of that- the planes, the lights that make clouded skies go red. I always ask myself: what's the biggest thing I can build, the thing people can see from the furthest away?